What would DNA sound if synthesized to an audio file

post, Jul 5, 2022, on Mitja Felicijan's blog

Introduction

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about the nature of life, what are the

foundation blocks of life and things like that. It's remarkable how complex and

on the other hand simple the creation is when you look at it. The miracle of

life keeps us grounded when our imagination goes wild. If the DNA are the blocks

of life, you could consider them to be an API nature provided us to better

understand all of this chaos masquerading as order.

I have been reading a lot about superintelligence and our somehow misguided path

to create general artificial intelligence. What would the building blocks or our

creation look like? Is the compression really the ultimate storage of

information? Will our creation also ponder this questions when creating new

worlds for themselves, or will we just disappear into the vastness of

possibilities? It is a little offensive that we are playing God whilst being

completely ignorant of our own reality. Who knows! Like many other

breakthroughs, this one will also come at a cost not known to us when it finally

happens.

To keep things a bit lighter, I decided to convert some popular DNA sequences

into an audio files for us to listen to. I am not the first one, nor I will be

the last one to do this. But it is an interesting exercise in better

understanding the relationship between art and science. Maybe listening to DNA

instead of parsing it will find a way into better understanding, or at least

enjoying the creation and cryptic nature of life.

DNA encoding and primer example

I have been exploring DNA in the past in my post from about 3 years ago in

Encoding binary data into DNA

sequence where I have been

converting all sorts of data into DNA sequences.

This will be a similar exercise but instead of converting to DNA, I will be

generating tones from Nucleotides.

| Nucleotides | Note | Frequency |

|---|

| A (Adenine) | A | 440 Hz |

| C (Cytosine) | C | 783.99 Hz |

| G (Guanine) | G | 523.25 Hz |

| T (Thymine) | D | 587.33 Hz |

Since we do not have T in equal-tempered scale, I choose D to represent T note.

You can check Frequencies for equal-tempered scale, A4 = 440

Hz. For this tuning, we also

choose Speed of Sound = 345 m/s = 1130 ft/s = 770 miles/hr.

Now that we have this out of the way, we can also brush up on the DNA sequencing

a bit. This is a famous quote I also used for the encoding tests, and it goes

like this.

How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of

making progress.

― Niels Bohr

>SEQ1

GACAGCTTGTGTACAAGTGTGCTTGCTCGCGAGCGGGTACGCGCGTGGGCTAACAAGTGA

GCCAGCAGGTGAACAAGTGTGCGGACAAGCCAGCAGGTGCGCGGACAAGCTGGCGGGTGA

ACAAGTGTGCCGGTGAGCCAACAAGCAGACAAGTAAGCAGGTACGCAGGCGAGCTTGTCA

ACTCACAAGATCGCTTGTGTACAAGTGTGCGGACAAGCCAGCAGGTGCGCGGACAAGTAT

GCTTGCTGGCGGACAAGCCAGCTTGTAAGCGGACAAGCTTGCGCACAAGCTGGCAGGCCT

GCCGGCTCGCGTACAAATTCACAAGTAAGTACGCTTGCGTGTACGCGGGTATGTATACTC

AACCTCACCAAACGGGACAAGATCGCCGGCGGGCTAGTATACAAGAACGCTTGCCAGTAC

AACC

This is what we gonna work with to get things rolling forward, when creating

parser and waveform generator.

Parsing DNA data

This step is rather simple one. All we need to do is parse input DNA sequence in

FASTA format well known in

Bioinformatics to extract single

Nucleotides that will be converted into separate tones based on equal-tempered

scale explained above.

nucleotide_tone_map = {

'A': 440,

'C': 523.25,

'G': 783.99,

'T': 587.33, # converted to D

}

def split(word):

return [char for char in word]

def generate_from_dna_sequence(sequence):

for nucleotide in split(sequence):

print(nucleotide, nucleotide_tone_map[nucleotide])

Generating sine wave

Because we are essentially creating a long stream of notes we will be appending

sine notes to a global array we will later use for creating a WAV file out of

it.

import math

def append_sinewave(freq=440.0, duration_milliseconds=500, volume=1.0):

global audio

num_samples = duration_milliseconds * (sample_rate / 1000.0)

for x in range(int(num_samples)):

audio.append(volume * math.sin(2 * math.pi * freq * (x / sample_rate)))

return

The sine wave generated here is the standard beep. If you want something more

aggressive, you could try a square or saw tooth waveform.

Generating a WAV file from accumulated sine waves

import wave

import struct

def save_wav(file_name):

wav_file = wave.open(file_name, 'w')

nchannels = 1

sampwidth = 2

nframes = len(audio)

comptype = 'NONE'

compname = 'not compressed'

wav_file.setparams((nchannels, sampwidth, sample_rate, nframes, comptype, compname))

for sample in audio:

wav_file.writeframes(struct.pack('h', int(sample * 32767.0)))

wav_file.close()

44100 is the industry standard sample rate - CD quality. If you need to save on

file size, you can adjust it downwards. The standard for low quality is, 8000 or

8kHz.

WAV files here are using short, 16 bit, signed integers for the sample size.

So, we multiply the floating-point data we have by 32767, the maximum value for

a short integer.

It is theoretically possible to use the floating point -1.0 to 1.0 data

directly in a WAV file, but not obvious how to do that using the wave module

in Python.

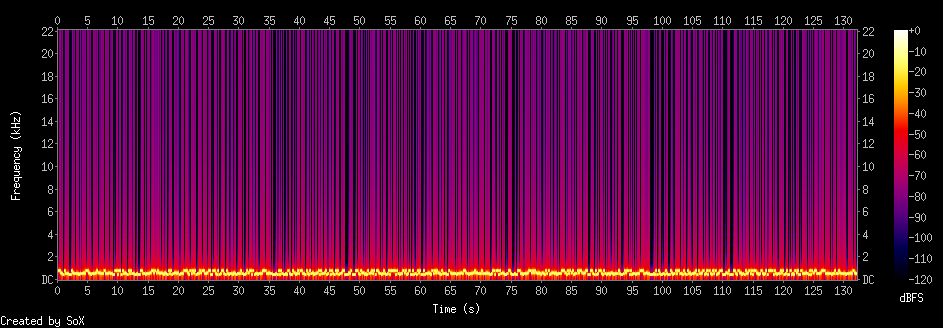

Generating Spectograms

I have tried two methods of doing this and both were just fine. I however opted

out to use the SoX - Sound eXchange, the Swiss Army knife of audio

manipulation one because it didn't require

anything else.

sox output.wav -n spectrogram -o spectrogram.png

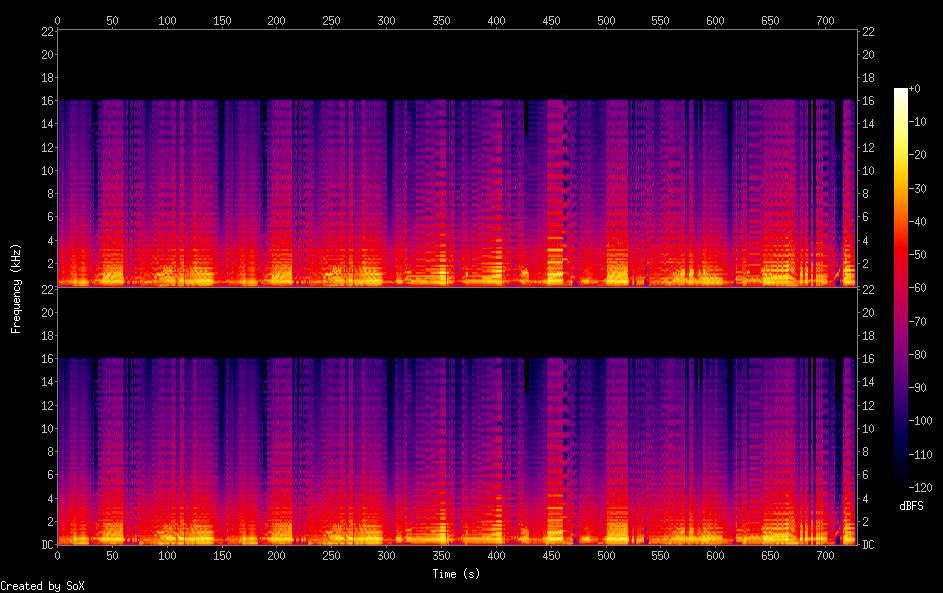

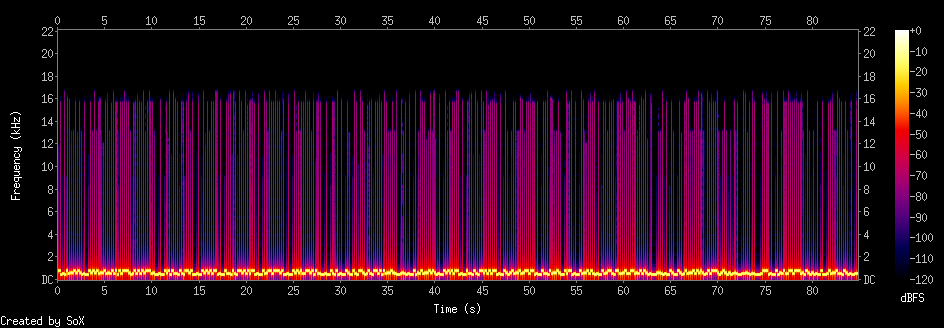

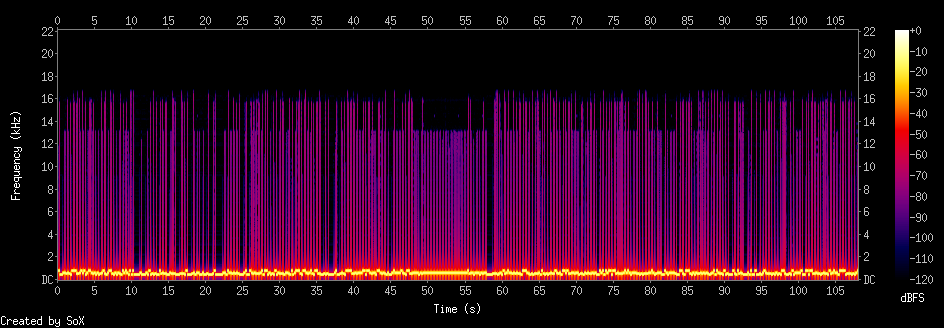

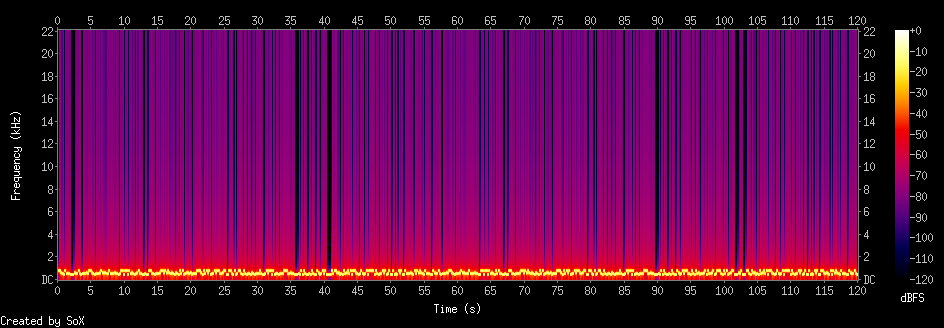

An example spectrogram of Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 6 First movement.

The other option could also be in combination with

gnuplot. This would require an intermediary step,

however.

sox output.wav audio.dat

tail -n+3 audio.dat > audio_only.dat

gnuplot audio.gpi

And input file audio.gpi that would be passed to gnuplot looks something like

this.

# set output format and size

set term png size 1000,280

# set output file

set output "audio.png"

# set y range

set yr [-1:1]

# we want just the data

unset key

unset tics

unset border

set lmargin 0

set rmargin 0

set tmargin 0

set bmargin 0

# draw rectangle to change background color

set obj 1 rectangle behind from screen 0,0 to screen 1,1

set obj 1 fillstyle solid 1.0 fillcolor rgbcolor "#ffffff"

# draw data with foreground color

plot "audio_only.dat" with lines lt rgb 'red'

Pre-generated sequences

What I did was take interesting parts from an animal's genome and feed it to a

tone generator script. This then generated a WAV file and I converted those to

MP3, so they can be played in a browser. The last step was creating a

spectrogram based on a WAV file.

Niels Bohr quote

Mouse

This is part of a mouse genome Mus_musculus.GRCm39.dna.nonchromosomal. You

can get genom data

here.

Bison

This is part of a bison genome Bison_bison_bison.Bison_UMD1.0.cdna. You can

get genom data

here.

Taurus

This is part of a taurus genome Bos_taurus.ARS-UCD1.2.cdna. You can get

genom data

here.

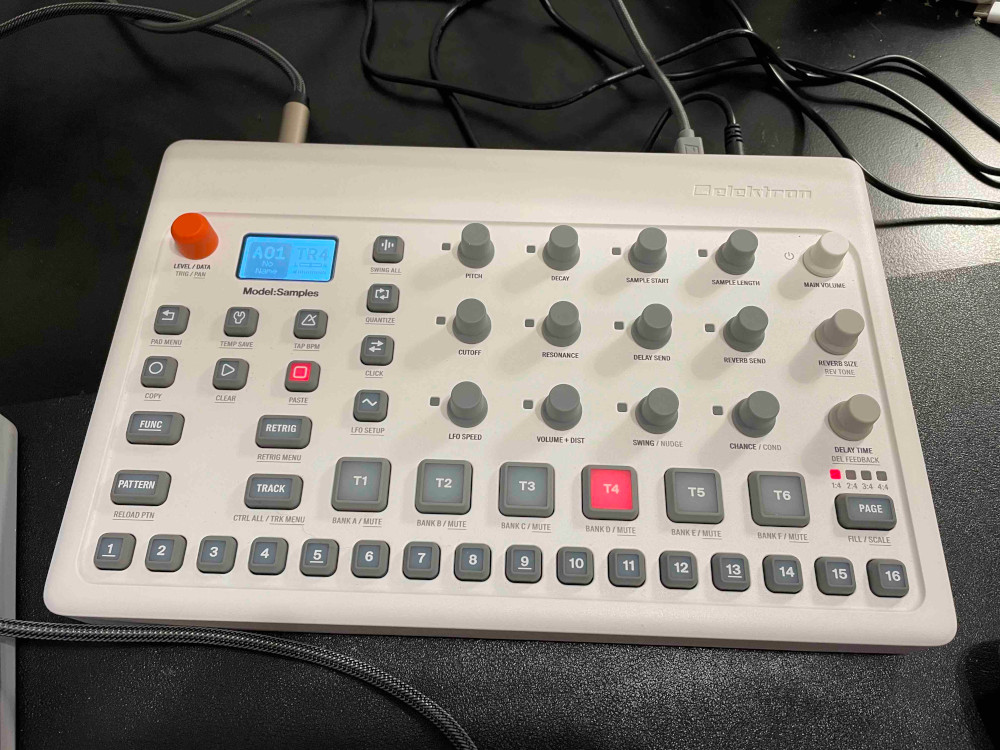

Making a drummer out of a DNA sequence

To make things even more interesting, I decided to send this data via MIDI to my

Elektron Model:Samples. This is a

really cool piece of equipment that supports MIDI in via USB and 3.5 mm audio

jack.

Elektron is connected to my MacBook via USB cable and audio out is patched to a

Sony Bluetooth speaker I have that supports 3.5 mm audio in. Elektron doesn't

have internal speakers.

For communicating with Elektron, I choose pygame Python module that has MIDI

built in. With this, it was rather simple to send notes to the device. All I did

was map MIDI notes to the actual Nucleotides.

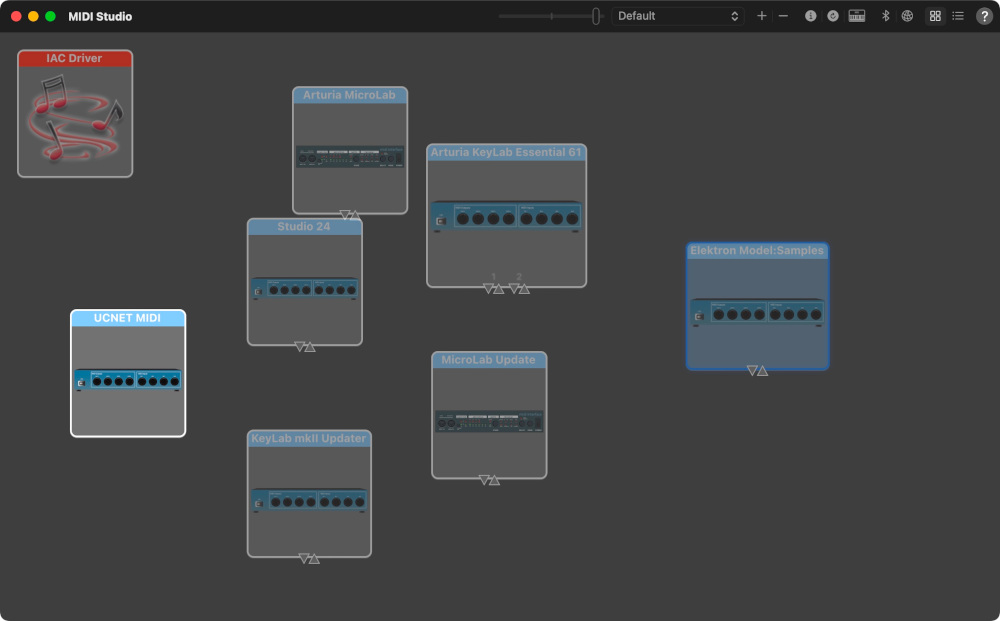

Before all of this I also checked Audio MIDI Setup app under MacOS and checked

MIDI Studio by pressing ⌘-2.

The whole script that parses and send notes to the Elektron looks like this.

import pygame.midi

import time

pygame.midi.init()

print(pygame.midi.get_default_output_id())

print(pygame.midi.get_device_info(0))

player = pygame.midi.Output(1)

player.set_instrument(2)

def send_note(note, velocity):

global player

player.note_on(note, velocity)

time.sleep(0.3)

player.note_off(note, velocity)

nucleotide_midi_map = {

'A': 60,

'C': 90,

'G': 160,

'T': 180, # is D

}

with open("quote.fa") as f:

sequence = f.read().replace('\n', '')

for nucleotide in [char for char in sequence]:

print("Playing nucleotide {} with MIDI note {}".format(

nucleotide, nucleotide_midi_map[nucleotide]))

send_note(nucleotide_midi_map[nucleotide], 127)

del player

pygame.midi.quit()

All of this could be made much more interesting if I choose different

instruments for different Nucleotides, or doing more funky stuff with Elektron.

But for now, this should be enough. It is just a proof of concept. Something to

play around with.

Going even further

As you probably notice, the end results are quite similar to each other. This is

to be expected because we are operating only with 4 notes essentially. What

could make this more interesting is using something like

Supercollider to create more interesting

sounds. By transposing notes or using effects based on repeated data in a

sequence. Possibilities are endless.

It is really astonishing what can be achieved with a little bit of code and an

idea. I could see this becoming an interesting background soundscape instrument

if done properly. It could replace random note generator with something more

intriguing, biological, natural.

I actually find the results fascinating. I took some time and listened to this

music of nature. Even though it's quite the same, it's also quite different.

The subtle differences on repeat kind of creates music on its own. Makes you

wonder. It kind of puts Occam’s Razor in its place. Nature for sure loves to

make things as energy efficient as possible.