Running Golang application as PID 1 with Linux kernel

post, Dec 25, 2021, on Mitja Felicijan's blog

Unikernels, kernels, and alike

I have been reading a lot about

unikernernels lately and found them

very intriguing. When you push away all the marketing speak and look at the

idea, it makes a lot of sense.

A unikernel is a specialized, single address space machine image constructed

by using library operating systems. (Wikipedia)

I really like the explanation from the article

Unikernels: Rise of the Virtual Library Operating System.

Really worth a read.

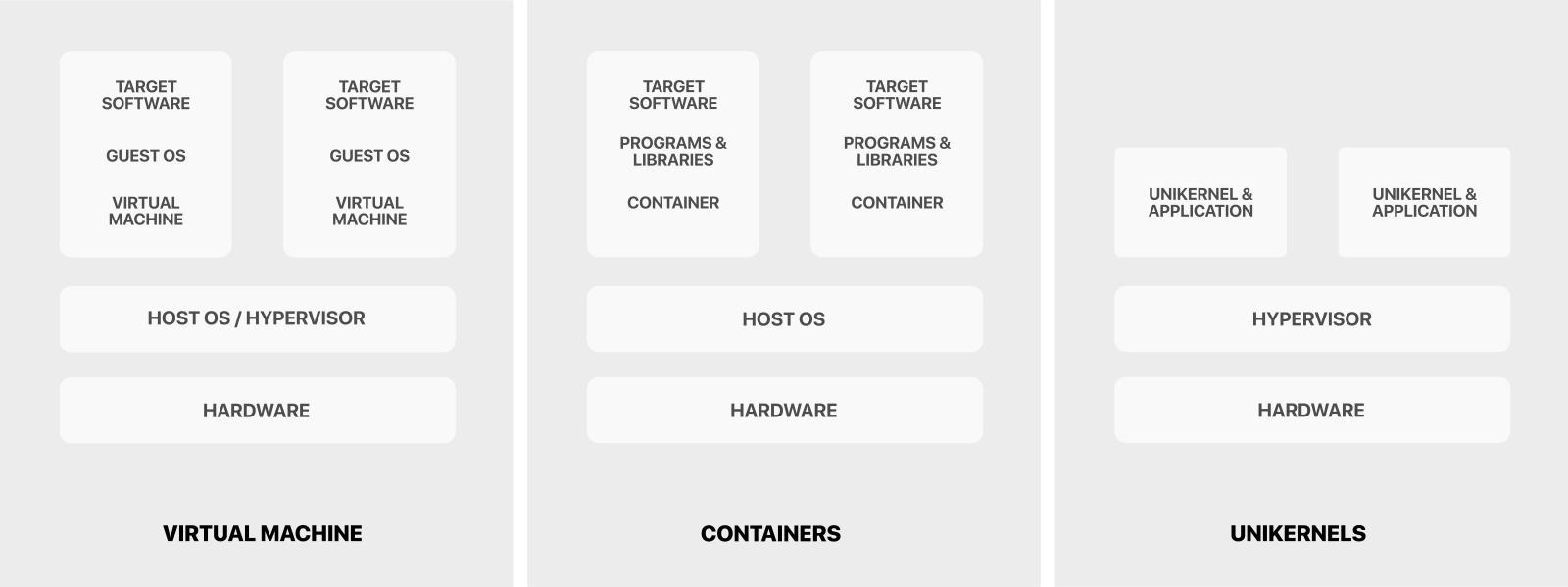

If we compare a normal operating system to a unikernel side by side, they would

look something like this.

From this image, we can see how the complexity significantly decreases with

the use of Unikernels. This comes with a price, of course. Unikernels are hard

to get running and require a lot of work since you don't have an actual proper

kernel running in the background providing network access and drivers etc.

So as a half step to make the stack simpler, I started looking into using

Linux kernel as a base and going from there. I came across this

Youtube video talking about Building the Simplest Possible Linux System

by Rob Landley and apart from statically compiling the

application to be run as PID1 there was really no other obstacles.

What is PID 1?

PID 1 is the first process that Linux kernel starts after the boot process.

It also has a couple of unique properties that are unique to it.

- When the process with PID 1 dies for any reason, all other processes are

killed with KILL signal.

- When any process having children dies for any reason, its children are

re-parented to process with PID 1.

- Many signals which have default action of Term do not have one for PID 1.

- When the process with PID 1 dies for any reason, kernel panics, which

result in system crash.

PID 1 is considered as an Init application which takes care of running other

and handling services like:

- sshd,

- nginx,

- pulseaudio,

- etc.

If you are on a Linux machine, you can check what your process is with PID 1

by running the following.

$ cat /proc/1/status

Name: systemd

Umask: 0000

State: S (sleeping)

Tgid: 1

Ngid: 0

Pid: 1

PPid: 0

...

As we can see on my machine the process with id of 1 is systemd

which is a software suite that provides an array of system components for Linux

operating systems. If you look closely you can also see that the PPid

(process id of the parent process) is 0 which additionally confirms that

this process doesn't have a parent.

So why even run application as PID 1 instead of just using a container?

Containers are wonderful, but they come with a lot of baggage. And because they

are in their nature layered, the images require quite a lot of space and also a

lot of additional software to handle them. They are not as lightweight as they

seem, and many popular images require 500 MB plus disk space.

The idea of running this as PID 1 would result in a significantly smaller footprint,

as we will see later in the post.

You could run a simple init system inside Docker container described more

in this article Docker and the PID 1 zombie reaping problem.

The master plan

- Compile Linux kernel with the default definitions.

- Prepare a Hello World application in Golang that is statically compiled.

- Run it with QEMU and providing Golang application

as init application / PID 1.

For the sake of simplicity we will not be cross-compiling any of it and just

use the 64bit version.

Compiling Linux kernel

$ wget https://cdn.kernel.org/pub/linux/kernel/v5.x/linux-5.15.7.tar.xz

$ tar xf linux-5.15.7.tar.xz

$ cd linux-5.15.7

$ make clean

# read more about this https://stackoverflow.com/a/41886394

$ make defconfig

$ time make -j `nproc`

$ cd ..

At this point we have kernel image that is located in arch/x86_64/boot/bzImage.

We will use this in QEMU later.

To make our lives a bit easier lets move the kernel image to another place.

Lets create a folder bin/ in the root of our project with mkdir -p bin.

At this point we can copy bzImage to bin/ folder with

cp linux-5.15.7/arch/x86_64/boot/bzImage bin/bzImage.

The folder structure of this experiment should look like this.

pid1/

bin/

bzImage

linux-5.15.7/

linux-5.15.7.tar.xz

Preparing PID 1 application in Golang

This step is relatively easy. The only thing we must have in mind that we will

need to compile the binary as a static one.

Let's create init.go file in the root of the project.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

for {

fmt.Println("Hello from Golang")

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}

}

If you notice, we have a forever loop in the main, with a simple sleep of 1

second to not overwhelm the CPU. This is because PID 1 should never complete

and/or exit. That would result in a kernel panic. Which is BAD!

There are two ways of compiling Golang application. Statically and dynamically.

To statically compile the binary, use the following command.

$ go build -ldflags="-extldflags=-static" init.go

We can also check if the binary is statically compiled with:

$ file init

init: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, Go BuildID=Ypu8Zw_4NBxm1Yxg2OYO/H5x721rQ9uTPiDVh-VqP/vZN7kXfGG1zhX_qdHMgH/9vBfmK81tFrygfOXDEOo, not stripped

$ ldd init

not a dynamic executable

At this point, we need to create initramfs

(abbreviated from "initial RAM file system", is the successor of initrd. It

is a cpio archive of the initial file system that gets loaded into memory

during the Linux startup process).

$ echo init | cpio -o --format=newc > initramfs

$ mv initramfs bin/initramfs

The projects at this stage should look like this.

pid1/

bin/

bzImage

initramfs

linux-5.15.7/

linux-5.15.7.tar.xz

init.go

Running all of it with QEMU

QEMU is a free and open-source hypervisor. It emulates

the machine's processor through dynamic binary translation and provides a set

of different hardware and device models for the machine, enabling it to run a

variety of guest operating systems.

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -serial stdio -kernel bin/bzImage -initrd bin/initramfs -append "console=ttyS0" -m 128

$ qemu-system-x86_64 -serial stdio -kernel bin/bzImage -initrd bin/initramfs -append "console=ttyS0" -m 128

[ 0.000000] Linux version 5.15.7 (m@khan) (gcc (GCC) 11.2.1 20211203 (Red Hat 11.2.1-7), GNU ld version 2.37-10.fc35) #7 SMP Mon Dec 13 10:23:25 CET 2021

[ 0.000000] Command line: console=ttyS0

[ 0.000000] x86/fpu: x87 FPU will use FXSAVE

[ 0.000000] signal: max sigframe size: 1440

[ 0.000000] BIOS-provided physical RAM map:

[ 0.000000] BIOS-e820: [mem 0x0000000000000000-0x000000000009fbff] usable

[ 0.000000] BIOS-e820: [mem 0x000000000009fc00-0x000000000009ffff] reserved

[ 0.000000] BIOS-e820: [mem 0x00000000000f0000-0x00000000000fffff] reserved

[ 0.000000] BIOS-e820: [mem 0x0000000000100000-0x0000000007fdffff] usable

[ 0.000000] BIOS-e820: [mem 0x0000000007fe0000-0x0000000007ffffff] reserved

[ 0.000000] BIOS-e820: [mem 0x00000000fffc0000-0x00000000ffffffff] reserved

[ 0.000000] NX (Execute Disable) protection: active

[ 0.000000] SMBIOS 2.8 present.

[ 0.000000] DMI: QEMU Standard PC (i440FX + PIIX, 1996), BIOS 1.14.0-6.fc35 04/01/2014

[ 0.000000] tsc: Fast TSC calibration failed

...

[ 2.016106] ALSA device list:

[ 2.016329] No soundcards found.

[ 2.053176] Freeing unused kernel image (initmem) memory: 1368K

[ 2.056095] Write protecting the kernel read-only data: 20480k

[ 2.058248] Freeing unused kernel image (text/rodata gap) memory: 2032K

[ 2.058811] Freeing unused kernel image (rodata/data gap) memory: 500K

[ 2.059164] Run /init as init process

Hello from Golang

[ 2.386879] tsc: Refined TSC clocksource calibration: 3192.032 MHz

[ 2.387114] clocksource: tsc: mask: 0xffffffffffffffff max_cycles: 0x2e02e31fa14, max_idle_ns: 440795264947 ns

[ 2.387380] clocksource: Switched to clocksource tsc

[ 2.587895] input: ImExPS/2 Generic Explorer Mouse as /devices/platform/i8042/serio1/input/input3

Hello from Golang

Hello from Golang

Hello from Golang

The whole log file here.

Size comparison

The cool thing about this approach is that the Linux kernel and the application

together only take around 12 MB, which is impressive as hell. And we need to

also know that the size of bzImage (Linux kernel) could be greatly decreased

by going into make menuconfig and removing a ton of features from the kernel,

making the size even smaller. I managed to get kernel size down to 2 MB and

still working properly.

total 12M

-rw-r--r--. 1 m m 9.3M Dec 13 10:24 bzImage

-rw-r--r--. 1 m m 1.9M Dec 27 01:19 initramfs

Creating ISO image and running it with Gnome Boxes

First we need to create proper folder structure with mkdir -p iso/boot/grub.

Then we need to download the grub binary.

You can read more about this program on https://github.com/littleosbook/littleosbook.

$ wget -O iso/boot/grub/stage2_eltorito https://github.com/littleosbook/littleosbook/raw/master/files/stage2_eltorito

$ tree iso/boot/

iso/boot/

├── bzImage

├── grub

│ ├── menu.lst

│ └── stage2_eltorito

└── initramfs

Let's copy files into proper folders.

$ cp stage2_eltorito iso/boot/grub/

$ cp bin/bzImage iso/boot/

$ cp bin/initramfs iso/boot/

Lets create a GRUB config file at nano iso/boot/grub/menu.lst with contents.

default=0

timeout=5

title GoAsPID1

kernel /boot/bzImage

initrd /boot/initramfs

Let's create iso file by using genisoimage:

genisoimage -R \

-b boot/grub/stage2_eltorito \

-no-emul-boot \

-boot-load-size 4 \

-A os \

-input-charset utf8 \

-quiet \

-boot-info-table \

-o GoAsPID1.iso \

iso

This will produce GoAsPID1.iso which you can use with Virtualbox

or Gnome Boxes.

Is running applications as PID 1 even worth it?

Well, the answer to this is not as simple as one would think. Sometimes it is

and sometimes it's not. For embedded systems and very specialized applications

it is worth for sure. But in normal uses, I don't think so. It was an interesting

exercise in compiling kernels and looking at the guts of the Linux kernel,

but sticking to containers for most of the things is a better option in my

opinion.

An interesting experiment would be creating an image that supports networking

and could be deployed to AWS as an EC2 instance and observing how it fares.

But in that case, we would need to write some sort of supervisor that would

run on a separate EC2 that would check if other EC2 instances are running

properly. Remember that if your application fails, kernel panics and the

whole machine is inoperable in this case.